note: this is part 2 of a two-part series examining how science fiction has directly and indirectly imagined aspects of the mobility revolution. Part 1 examines modern manifestations from the past 500 years. Part 2 examines ancient and medieval precursors from 500 BC to 1500 AD. These two posts are not comprehensive, just brief surveys of a few relevant works from across the centuries.

At first glance, a category like ancient science fiction might seem paradoxical. Most contemporary discussions of science fiction tend towards movies, TV shows, and fictional stories from the past 50 to 100 years—with the early part of that period being called the golden age of the genre. But authors around the world were already including familiar sci-fi elements in plays and poems over 2000 years ago.

Some of these elements—and how they were handled during technologically simpler times—may seem more reminiscent of contemporary fantasy. That genre typically involves impossibilities, such as paranormal activity, supernatural elements, and magic. Meanwhile, modern definitions of science fiction usually include technology and scenarios deemed possible based upon current theories and hypothetical inventions. But the sharp distinction between fantasy and sci-fi is more of a modern argument and potentially related to the rapid technological advancements during the industrial and digital revolutions. So how did the ancient and medieval precursors to modern science fiction imagine aspects of the mobility revolution? And what might we learn from those imaginings?

Precisely when the science fiction genre begins is widely debated. Some observers have pointed as far back as the Epic of Gilgamesh, from around 2000 BC, due to themes of immortality and apocalypse. Others point to roughly the 5th century BC, when a variety of sci-fi elements appear in several ancient works.

The Hindu epic poem Ramayan tells the story of a divine prince struggling to rescue his wife from the demon king, Ravana. In the poem, Ravana travels on a pushpaka vimana, which is described in various Sanskrit and Jain texts as being either a flying chariot or palace. In Ramayan, Ravana’s pushpaka vimana is described as resembling “the Sun…that aerial and excellent Vimana going everywhere at will…resembling a bright cloud in the sky…” Sometimes these vehicles are controlled by thought, while other times they are self-flying. Such features call to mind modern sci-fi elements like brain-computer interfaces and automated flying cars like a recent concept project from Airbus.

In 414 BC, ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes unveiled his comic play, The Birds, at the City Dionysia, an Athenian dramatic festival and competition. In the play, a civilization of avian humanoids builds a floating city called Cloudcuckooland in order to supplant the gods of Olympus and obtain dominion over men. Some observers have interpreted The Birds as a satire directed toward war-happy Athenians engaging in yet another questionable campaign, this time in Syria. Regardless, the concept of floating cities is a common sci-fi element, somewhat similar to the floating mountains of James Cameron’s 2009 film Avatar. Meanwhile, avian humanoids are another recurring feature of science fiction—such as the winged mutant Archangel in the X-men franchise.

Similar to avian humanoids, mechanical birds are a frequent element of ancient literature. These constructed automata are described in various texts, from the Sanskrit hymn Rigveda to the medieval Dutch story The Romance of Walewein. Archytas, an ancient Greek philosopher and mathematician born in the 5th century BC, was credited by later scholars for designing and building the first mechanical bird. Supposedly Archytas’ bird was powered by steam and flew 200 meters. While the claims may be hearsay, such references at least indicate that people were imagining antecedents to modern drones beginning 2,500 years ago.

Robots in general have a long lineage of historical imaginings. Several stories compiled over centuries in One Thousand and One [Arabian] Nights feature robots and automated horses, somewhat reminiscent of contemporary developments in the mobility revolution. One story, The City of Brass, tells of an archeological expedition to find a lost city and genie’s vessel. Along the way, expedition members encounter a brass horseman and activate it following instructions engraved on its lance. The robot leads the team to the abandoned city—calling to mind modern efforts toward automated navigation.

In the 14th century, so-called Father of English Literature, Geoffrey Chaucer, wrote a short story called “The Squire’s Tale” that includes a brass horse. The horse can carry riders anywhere in the world at fantastic speeds on voice command—a feature which is frequently envisioned for self-diving cars of the future. And roughly 100 years later, at the end of the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci was sketching designs for a robot knight. Only discovered in the artist’s notebooks during the 1950s, da Vinci’s robot includes a suit of armor and inner mechanics.

Surveying ancient and medieval sci-fi—albeit briefly and incompletely—reveals several intriguing trends. Millennia before the industrial and digital revolutions would introduce modern technologies necessary for the mobility revolution, philosophers and artists were engaged in futurism strikingly similar to modern engineers and scientists. But the imaginings of the ancients were constrained by the technologies and transportation methods of their own times.

Instead of quad-copter drones, mechanical birds hovered over imagined skies. Instead of self-driving automobiles, there were thought-controlled chariots and automated horses. Robots were made of brass, not stainless steels of the 19th century or carbon-fibers of the 21st. But the dreamy insistence on futurism—the desire to imagine what’s possible in a limitless fashion—was much the same as today.

And, if there is a lesson for the mobility revolution in ancient sci-fi, perhaps it’s that the one limiting factor of futurism is the same today as it was thousands of years ago. No one knows exactly what the future will look like. Will autonomous cars someday hover over magnetic tracks? Will future vehicles zoom over the earth like robot horsemen or take to the skies like pushpaka vimana? Which aspects of the future, as we imagine it today, will come true? Which aspects will fade into history, like the chariot?

In the meantime, practitioners of the mobility revolution continue to dream about what’s possible, much like ancient philosophers once did. And like da Vinci with his notebooks, today’s practitioners draw up plans and ponder, how can we build that?

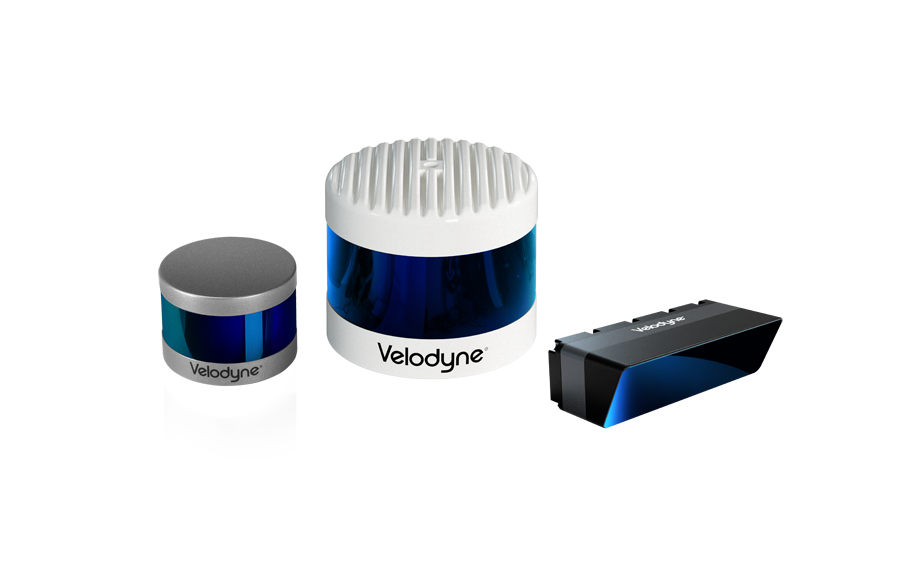

Velodyne Lidar (Nasdaq: VLDR, VLDRW) ushered in a new era of autonomous technology with the invention of real-time surround view lidar sensors. Velodyne, a global leader in lidar, is known for its broad portfolio of breakthrough lidar technologies. Velodyne’s revolutionary sensor and software solutions provide flexibility, quality and performance to meet the needs of a wide range of industries, including robotics, industrial, intelligent infrastructure, autonomous vehicles and advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS). Through continuous innovation, Velodyne strives to transform lives and communities by advancing safer mobility for all.