his is part 1 of a 2-part series examining how science fiction has directly and indirectly imagined aspects of the mobility revolution. Part 1 examines modern manifestations from the past 500 years. Part 2 will examine ancient and medieval precursors from 500 BC to 1500 AD. These two posts are not comprehensive, just brief surveys of a few relevant works from fiction, film, and television.

Ask a dozen sci-fi fans to define the characteristics and time period of the genre and you’ll likely get more than a dozen different answers. Modern science fiction has evolved over centuries to include countless cross-genres and subgenres: the retrofuturism of steampunk, often attributed to Jules Verne; the dystopian bleakness of tech noir, i.e. Blade Runner; the unexplained paranormal of science fantasy, including mid-20th-century pulp rags like Startling Stories or Weird Tales.

Despite such diversity, many observers agree on a few basic elements, including technological advancement, scientific discovery, societal change, and future prediction. Sound familiar? Such elements are strikingly similar to the pursuits of hardware, software, and engineering companies working diligently toward the mobility revolution. So, how has science fiction imagined various aspects of that revolution, from driverless vehicles to artificial intelligence to human-robot interactions? And what can we learn from such imaginings?

In 1516, the English author Thomas More wrote a puzzling satirical novel in Latin titled Utopia. On the island of Utopia, communistic aspects, such as no private property and communal goods shared by all, intermingle with authoritarian elements like lack of privacy and universal slavery—with the enslaved including foreigners, criminals, and, oddly, locals who forget to carry their passports while traveling.

While the term utopia has since come to mean an idealized or perfect society, More derived the word from the Greek οὐ (for not) and τόπος (for place), meaning no-place, or an impossibility. While the novel doesn’t include technological advancements, a key element of modern sci-fi, it includes plenty of socio-political change. More’s Utopia gave rise to the pervasive dystopian/utopian subgenres of today, which often include various imaginings of the mobility revolution, including autonomous and flying vehicles, advanced artificial intelligence, and pervasive sensing systems.

It’s worth noting that modern automobiles didn’t appear until 1885, with the invention of the Benz Patent-Motorwagen in Germany, and didn’t become widely available until the early 1900s with the Ford Model T. Thus, it seems many aspects of the contemporary mobility revolution remained indirectly imagined until the early 20th century. However, during centuries prior, other manifestations emerged, such as robot horsemen, mechanical birds (both discussed in part 2), and flying sea vessels.

In 1726, Jonathan Swift wrote Gulliver’s Travels, which includes a flying island named Laputa. The circular island has a circumference of 4.5 miles and 200-yard baseplate of adamantine—a word derived from Greek meaning any very hard substance, which has become a common name for imagined materials in science fiction. Similar to modern maglev trains, Laputa floats by magnetic properties over the rocky realm of Balnibarbi. During war, they drop rocks similar to modern ICBMs.

Many observers cite Jules Verne as a founder of modern science fiction. Writing from 1850 to 1905, Verne is credited with predicting many inventions of the modern age. Authoring over 60 books, Verne himself disputed he was a prophetic futurist, instead claiming he performed extensive research into what was scientifically possible given the knowledge of his time.

Among Verne’s technological imaginations was the submarine Nautilus in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1870). Based upon two real-life submarines—a hand-crank sub from 1800 and a compressed-air mechanically-propelled sub from 1863—Verne opted to have his Nautilus powered by electric batteries. This not only calls to mind modern deep-sea submersibles but also the current movement toward hybrid and fully electric vehicles, which are considered prime candidates for eventual automation. Other technological innovations Verne wrote about include video broadcast news, tasers, and flying cars in his 1904 novel Master of the World.

Science fiction involving automobiles—whether autonomous, sentient, or flying—proliferated at a seemingly exponential rate throughout the 20th century. The 1930 novel Paradise and Iron by Miles Breuer was among the first to imagine autonomous vehicles. Originally serialized in Amazing Stories Quarterly, the novel involves a visit to an island where everything is automated, including ocean vessels and city machinery.

The mid-20th century—with the exact timeframe up for debate—is commonly called the Golden Age of Science Fiction. One famous writer of the period was Isaac Asimov, who prolifically authored or edited over 500 books. His 1953 story “Sally” predicted that the only cars allowed on the roads of 2057 would have self-driving positronic brains. In the story, these cars fight back and kill a criminal to protect their care-taker.

The plot of “Sally” directly contradicts one of Asimov’s most famous imaginations, his Three Laws of Robotics related to governance of artificial intelligence. Various versions of the three, sometimes four, laws appear throughout Asimov’s fiction and basically include 1) robots must not harm humans nor allow humans to be harmed, 2) robots must obey human commands, 3) robots must protect their own existence without violating the first two laws, and 4) robots must offer the same protections to humanity in general. Contemporary efforts to develop artificial intelligence that will guide autonomous vehicles are grappling with similar questions of robot governance and rules.

The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) into mainstream science fiction coincided with the invention and rapid development of digital computers during the second half of the 20th century. Sometimes this intelligence was linked to driverless cars, like Sally, while other times it was related to increasingly complex and adventurous exploits like travel through time or space.

One of the most famous examples of artificial intelligence is Hal from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Based on Arthur C. Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel,” 2001 was simultaneously developed in the late-1960s as a novel by Clarke and a film by Stanley Kubrick. The heuristically programmed algorithmic computer, aka Hal, is a voice-interfacing sentient computer, capable of reasoning autonomously, piloting the spacecraft, and playing chess. The image of Hal’s camera lens eye, with a central red dot, has become synonymous with AI. Hal’s lasting cultural impression relates to his villainous role in the film. Hal assumes control of the ship, kills one astronaut, and disables life support before being disconnected.

A modern example of a sentient autonomous car is KITT from the 1980s TV show Knight Rider. Short for Knight Industries Two Thousand, KITT is a cybernetic computer controlling a technologically modified Pontiac Firebird Trans Am. KITT is fully capable of self-driving, but he serves more in a side-kick role to crime fighter Michael Knight, played by David Hasselhoff. KITT is an example of an on-demand fully autonomous vehicle that today would be categorized as level 5 in the 5-category SAE system. Lesser-known from the show is KITT’s precursor KARR, an antagonistic autonomous car that is dangerous and unstable due to being errantly programed for self-preservation.

As the millennium approached, countless imaginations of the mobility revolution filled science fiction. The Back to the Future trilogy (1985 to 1990) includes many elements, from a flying DeLorean time machine to news camera drones and autonomous hovering dog walkers. Total Recall, a classic 1990s body count action film, comically imagines an autonomous taxis as the wisecracking robot Johnny Cabs. The Fifth Element (1997) has art deco stylized flying cars with on-demand automatic modes. Based on a short story by Phillip K. Dick, 2002’s Minority Report features autonomous maglev vehicles that move in three dimensions along dedicated tracks. And the Asimov-inspired i, ROBOT has on-demand autonomy in a more realistic ground-based concept car designed by Audi—plus a robot rebellion against humans.

Throughout many of these imaginations of the mobility revolution, two intriguing trends emerge. First, there’s typically an inattention or simplification of the how. Understandably, science fiction is about entertainment, so the dramatization of what imagined technologies might do supplants how those technologies will work. Meanwhile, the backstory behind how a dystopian or utopian society came to exist is usually reduced to a vague reference of some catastrophic or revolutionary event in the timeline’s past. This first trend seems to lead to the second—there’s often a great deal of fear and cautionary concern associated with technological developments related to the mobility revolution.

Regarding the first trend, in science fiction, the underlying machinations that operate imagined technologies are typically omitted. How robots will see or sense is typically taken for granted—somehow, they just do. The practical concerns of the mobility revolution, such as which sensors—lidar, radar, optical, etc—will be used in which ways for autonomous sensing is understandably breezed over in most science fiction, where storytelling is the primary concern. Sometimes the how is handled with obfuscating jargon, such as Back to the Future’s “flux capacitor” or the now legendary and entertaining technobabble of the Star Trek universe—“dekyon field fluctuation,” anyone?!

But increasingly, as the technology of today comes to more closely resemble science fiction of the past, it seems more real science is being dramatized on the screen. For Minority Report, director Steven Spielberg convened a three-day think tank of 15 scientific experts to forecast realistic technologies for 2054. And in 2012’s Prometheus, a fictional crew in the late-21st century releases lidar-like drones to map a tunnel—a mapping technology that became viable only a few years after the movie’s release.

Perhaps the second trend—a pattern of fear toward technology—is where any lessons might be extracted for the mobility revolution. If so much of science fiction involves satirical commentary or apocalyptic concerns related to future technology, then practitioners should address such fears through transparent and clear communication about their goals and efforts. If so many imaginings involve self-driving cars run amok, like Stephen King’s Christine or Maximum Overdrive, and dystopian robot wars, like in the Terminator franchise, then practitioners must treat such fears seriously and discuss the safeguards being planned and implemented.

If the dihydrogen monoxide hoax—where the chemical name for water is used to make the substance sound different and threatening to laypeople—is any indication, extensive use of jargon can be alienating, possibly even threatening. It seems that when the benefits of the mobility revolution—especially regarding increased safety and reduced road accidents—are conveyed clearly and openly, observers respond positively. Sentient cyborgs declaring war on humanity are still a long way off from even being remotely possible. But in the short term, regarding autonomous vehicles, the sky seems the limit. And perhaps, someday, cars like those in The Jetsonswill fly autonomously, too.

Thank you to the Velodyne team for their input during research for this post! Keep an eye out for part 2, which will look at ancient and medieval science fiction precursors relevant to the mobility revolution!

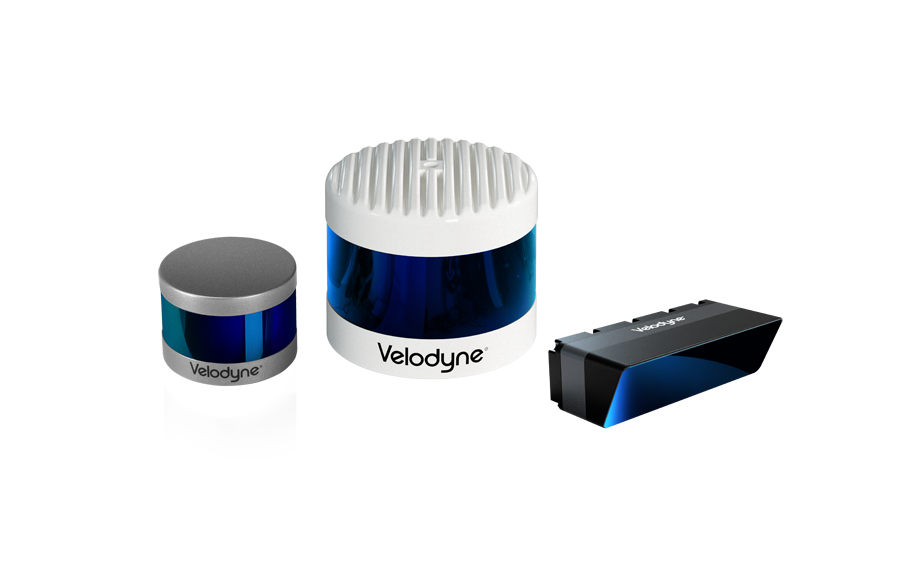

Velodyne Lidar (Nasdaq: VLDR, VLDRW) ushered in a new era of autonomous technology with the invention of real-time surround view lidar sensors. Velodyne, a global leader in lidar, is known for its broad portfolio of breakthrough lidar technologies. Velodyne’s revolutionary sensor and software solutions provide flexibility, quality and performance to meet the needs of a wide range of industries, including robotics, industrial, intelligent infrastructure, autonomous vehicles and advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS). Through continuous innovation, Velodyne strives to transform lives and communities by advancing safer mobility for all.